The Magic of Alaska

Written by Jerzy Marcin

At last, the day of my 2022 trip to Alaska came. After a whole night crossing the North American Continent first to Anchorage and then on to Juneau, my Alaskan Airline plane landed. While we were still on the tarmac taxing to the terminal, I peeked out the window. The weather looked very hopeful with puffy white clouds racing across a picture perfect blue sky.

By the time I picked up my bags and got out of the airport, the blue sky was all gone. In its place were dark heavy clouds. I could see a wall of rain in the distance. It was early June in Southwest Alaska. The weather could have been worse.

Unwilling to spend over 200 dollars on a crummy Juneau area hotel, I had booked a tent site at a local campground. Getting there meant I had to hunt for a taxi. Taxis, in this part of Alaska, are a dying breed. I went to a taxi stand in hopes of finding one there. No one else was bold enough to come out in search of a ride.

Within minutes, instead of a taxi, rain arrived. Patiently waiting in a cold merciless downpour, I kept my eyes wide open just in case some lost soul would come around to take me out of this misery. I became numb and quite desperate. If I had to, I would even hitch a ride with a complete stranger.

My determination was not in vain. An hour or so later, I heard an engine misfire, and then an old jitney van came thundering down the parking lot. It was a true beater, sputtering exhaust everywhere but still alive and ready to take me anywhere my heart desired. Waving both of my hands in the air, I desperately hailed it down. The beast came to a screeching halt, its doors flung open, and all my kit vanished inside its cavernous hold. A bony Native American taxi driver beckoned me to get inside. Off we went.

Puttering along a 10 mile long narrow winding highway in the Tongass National Forest took a good half hour. The last stretch led up a steep incline. We were atop an overgrown rocky bluff, on the Auk Village Campground service road. I spotted a myriad of tiny islets sticking out of the sea cove below. A strong sea breeze tossed some breaking waves over the rocky outcroppings. It was still misty and very wet. The old jalopy labored along the muddy track at times spinning its wheels violently. Then, we cleared the last slippery bend in the narrow road and pulled into my campsite.

As if by magic, the rain stopped when I pulled my bags out of the van to put them under a tall camping table. The driver waved goodbye and spun around in the direction of the main road. The thundering racket of the old clunker vanished quickly.

The weather turned foul again. Dark heavy clouds moved in as sheets of rain completely obscured the view. Down below, I heard pounding waves furiously slamming the shoreline. I hunkered down under the table and sat on my soggy bags. The wind whirled, the rain splattered everywhere. I regretted not getting a hotel room. It was too late.

An hour went by, and the rain abated. It was my call to action before the angry weather struck again. Quickly, I stuffed my food in the camp vault and sat off on a safety check of the area. Once I found no signs of bear activity, I pitched my tent on the wet mossy ground.

The fog lifted, unveiling the beauty of Alaska. I sat out on a nearby rock staring down at the ocean below. Furious waves exploded on the kelp laden coastline. Out in the distance I could make out the lights of the ferry terminal. It was time to hit the sack. Later that night, as the relentless wind tore at the tent fly, it blew away all my aches and worries. I drifted into a sound, well deserved slumber and heard absolutely nothing till I woke up to a picture perfect sunrise the following day.

Ferryboat To Gustavus

My alarm rang at 5a.m. The sun had risen 2 hours before. I struck down my camp and called for a taxi. After a few rings, I knew it was futile. In vain, I tried all the Google suggestions listed under Juneau Taxi. Hoping for a miracle, I tried it one more time, calling them one by one once again. Hopefully someone would come to the phone. I called and called but to no avail. At last, I heard a hoarse raspy voice come in on the other end of the line. An old man answered the call. He agreed to be my driver to the ferry terminal.

By 8 a.m., I sat down in a large boat compartment for a four hour ferry ride to Gustavus. Meandering in and out of the open sea, the boat passed a tundra covered procession of rugged islands. Home to no one else but nature itself, these islands eventually gave way to the vastness of the shimmering gray ocean. Rocked by the gentle waves and humming along to the tune of a massive diesel engine, the old ferry creaked ominously.

Up ahead, whales sprung up out of the murky water. The pungent ocean breeze filled my nostrils as I went out on a foredeck for a walk. As if by command, eye piercing sunbeams sliced through the thick clouds overhead. In mid air over the bow, a flock of rowdy seagulls mewed violently looking for scraps.

Cast Away

At noon three days later, I left Bartlett Cove, the getaway for Glacier Bay National Park just outside the port city of Gustavus. There are no roads in the park. The only access to this protected area is by a boat or a floatplane. I used my 16 foot long foldable Oru origami kayak that I had brought with me from Chicago. My destination, Riggs Glacier, was hidden behind an unknown number of days.

The 70 or so miles that separated me from my goal stretched over open bays and narrow sea passages studded with underwater obstacles. At the mercy of nature, my trip was to take me into the world where wild animals rule. At the end of my journey was a deep narrow fjord known as the East Arm. Somewhere there, I would turn around to head back to Bartlett Cove.

Paddling hard into the wind, I entered a narrow cut leading to the first island camp on my journey. The current was swift and at times it would totally overpower me. I used the reverse flow of the eddies to move up ahead. My sore muscles screamed as I battled for every inch. The rainy mist cooled me off so that my heart would not explode. Then came my break. The tide switched. It grabbed me from behind, forcing me out on a roller coaster ride towards the opposite end of the cut.

It was early evening by the time I was spat out of the cut. I mustered all my strength to turn towards the Archipelago of Beardsley Islands. I strained my eyes to see where it was. At first, all I saw were flocks of white water birds bobbing up and down. Dazed and exhausted, I was too confused to even think to look at the map. I just kept on paddling into the open sea ahead. A flicker of light broke through the haze. The evening breeze brought the sun out of the dark clouds. I saw green tuffs dotting the horizon. There, somewhere in the midst of this quagmire maze of land and water, was an island that was not a bird sanctuary. I had to find it fast, long before darkness so that I would have time to find a safe refuge for the night.

Dancing Waters

My island was there just as it was promised. Once I cleared all the bird sanctuaries and made all the right turns, I literally stumbled over it. There was a problem though. As I started unloading my stuff, an old lady flew out of the woods waving a stick in her wrinkly hand. She informed me that she and her friends had already established a camp there and told me that the island belonged to them and I was not welcome to share their nightly sabbath. I obediently threw everything back into my kayak.

Before I even had time to sit down in my cockpit, the crone shoved me out into the quickly descending darkness. I screamed as a sharp boulder slit the bottom of the plastic fold of the kayak skin. Disgusted with the whole situation, I resumed my search for a place to sleep, even though water started seeping in.

The leak must have been small. I felt numbing cold water oozing down from the bow and slowly accumulating in the cockpit. I steered the boat straight into the treacherous Sitakaday Passage up ahead. There, in the purple glow of the late night summer sun, was Strawberry Island. At first glance it looked like a half hour jaunt across a red carpet of placid waters punctuated by standing waves. If only I could punch through and around the whirlpools without being sucked into their ominous grip. Locking my hands on the cold drippy paddle shaft, I squeezed through dodging all the obstacles to the northern tip of the island.

As I drew nearer, I knew I could not come ashore. A dark, boulder strewn beach loomed high above me. The ocean tide washed around Strawberry Island as it raced down into the upper bay offering me no place to land there safely. I had to retrace my steps back to any one of the non-restricted islands in the Beardsley Archipelago.

As the sun plunged behind the Fairweather Range, darkness fell rapidly. In the dying light, I could barely make out the jagged wave peaks that marked the location of Sita Reef up ahead. The foreboding and overpowering current dragged dangerously close. Sweat poured over my weary back as I realized that it was too late to gain any ground by backpaddling. The only option was to face the danger headfirst. I had to muster enough strength to outmaneuver the roaring rapids by extracting myself from the collision course that I was on. My hands were numb, I fumbled with the switch to turn my headlight on. I had to be able to scan for whirlpools.

I vigorously dug into the racing water with just the left paddle blade while clutching the shaft at the throat of the right side. By overextending the paddle to the left, I added extra torque to the left side of the paddle. I had to somehow counteract the pull of the overpowering tidal current. Otherwise, I would have drifted straight into the mayhem of the Sita Reef. Beating the odds at last, I veered away from the main channel of the Sitakaday Narrows.

Waves roared all around me. Their frothing white foam glared at me in the beam of the headlight. Playing Russian Roulette with them, I rode barrels of icy seawater not knowing if these mounting waves would pounce on me from behind. How I wished I had eyes in the back of my head. I could not turn around lest I would tumble sideways or run into a whirlpool.

A tense hour crawled by. Clinging to my life at all costs, I kept yelling and screaming to boost my fading ego. Constant zig zagging around wicked waterholes, avoiding wave-breaking shoals, and outrunning the gut-churning surf behind me, wore me out to the bone.

In the end, I beat all the odds and kept the kayak going in the direction of the Beardsleys. There, in the light of the rising moon, was Fox Farm Island. Miles away at first, it gradually came to view as I bucked up and down in the rapidly moving current. Minutes later, a cold blustery breeze grabbed me from behind. I just rode with it without letting the stern of the kayak slip to the side.

A few more desperate strokes brought me around another reef. Then, the back of the boat perilously Iifted. I lurched up and then leaped forward. I was surfing on top of a galloping wave. I paddled hard so as not to be outrun. The end was near. Over the roaring seas, I saw a tiny beach coming at me fast. For a split second, the kayak stalled, then I picked up speed again. The whole ocean roared. To the left of the kayak, the wave I was riding on began to peel violently. The bulging surf turned me sideways. I spun the kayak back and pointed it straight again. Seconds later, I ran aground on the beach pebbles. The waves pushed me further up. I yanked the spray skirt off. As I got out, water rushed in through the gaping hole in the cockpit. I grabbed the heavy kayak and dragged it away from the brutal surf.

Dead tired, I was on dry land at last. I checked my GPS for my location. One quick glance confirmed that I was indeed on Farm Island. I looked around, there was a large meadow right above the tidal zone. I unzipped the kayak to get the load out. Then, I bailed the water out with the kayak pump. I hauled the empty boat and all my belongings up a steep shore. Soon in my tent, I was fast asleep, oblivious to the fact that this island might be my last one since I had a hole somewhere in the bow.

Rude Awakening

Early in the morning, an alarming low, thunderous growl pierced my sleep. I screamed. Was it a giant grizzly? Mortified, I got ready. I armed myself with the flare gun in one hand and the bear spray in the other. I hung by the mesh door. My tormentor struck again. I sighed with relief. It was not a bear, but a tiny hummingbird whirling around my vestibule. The hummingbird’s feathers vibrated the air emitting this metallic throbbing sound. Oddly enough, it was a soothing sound after all.

Awakened by my ‘near-death experience’ with the feathery rascal, I had no chance to go back to sleep. The day was already in full swing. Busily chattering in the tree canopy above, bold eagles jostled for position. The persistent caw, caw calls reverberated the still air signaling to me that the ravens desired to have me off the island. Buzzing violently at the tent door, hungry mosquitos were impatiently waiting for their daily meal. Out in the distance, whales gasped loudly for air.

It was still too early for my aching body to roll out of the tent. Afterall, the check out time was at noon, the time that the ocean tide would be most favorable. That was not for another four hours. Reluctantly, I stuffed my sleeping bag and stepped out into the blinding light. Blood sucking mosquitoes covered my clothes. Curious about the weather, I peeked at the ocean through the thick wall of underbush. Not a wrinkle, just silky blue water under a cloudless sky.

It was time to get busy. I turned the kayak over, dried the damaged fold with my dirty socks and doused the hole with rubbing alcohol. I slammed the sticky patch on top of it and the kayak was good as new. Had the hole been an inch closer in the trifold section of the bottom of the kayak, I would not have been able to patch it at all. By noon, I was riding the incoming tide cutting across the smooth blue ocean.

The run in with the ill-mannered hummingbird, was just one of the countless interactions I had with the wild animals. There were times when I only saw their traces. Signs of the animals that had been there but hid in the thicket or dove in deep water just before I came. Either on land or on water, I was never truly alone. Occasionally, pesky sea lions almost brushed against the thin skin of the kayak. In the rare stillness of some nights, I heard whales singing songs to one another. Looking up at the sky for clues about the weather, I saw a ceaseless procession of colorful birds on the move.

Stranded

A few days later, while I was marooned at the Spokane Cove waiting for an impending windstorm, I spotted numerous wolf and grizzly tracks and dreadful piles of scat everywhere. Though it was terrifying, it was perfectly normal. It was already too late to go anywhere else. Terrified of being blown away in the wind storm later that night, I had no choice but stay put. I stashed the kayak in the thick bushes on the high riverbank. Then, I hid the two bear vaults with food for the next two weeks under a heavy log.

As I was scouting the area for a safe place to spend the night, I heard a flock of marbled murrelets scream in alarm. What was it, I wondered. Why all that racket? Then, a pair oystercatchers tried for the last time to run me off the area with their aerial antics. Hardly any light filtered through the heavy clouds above. In this semi darkness, every brown rock was a grizzly bear. Leary at first, I had to stamp out my fear. I had no one or nowhere to run for comfort or protection.

A few moments later, it became very humid. Right over my head, dark ominous clouds piled up into the shape of a giant hair roller. For an instant, everything stopped moving, even the thick air stood completely still. This eerie silence placated all the living creatures. Huddled in their hiding places they knew only too well what was about to come.

Then, all hell broke loose. Out of the sea, a vile, wicked gale swept over the land. The wild storm took command, tearing down all dried out tree branches, leaves, silt and ripping out all dead grasses. Trees buckled, wavered, moaned begging for a reprieve. A ghostly red cedar skeleton cracked loudly and then buckled as it tumbled down with its roots torn away.

I frantically began setting up my camp in a meager clearing tucked away from the path of destruction. As I laid the tent down on the scrawny grass, the wind gust almost ripped it out of my hands. I painstakingly fought to stake it down in the rocky ground. At last, the tent was standing strong. I crawled inside through the narrow entryway. The tent canopy began breathing in and out the seabourn fury mimicking a jellyfish swimming in the sea.

Within minutes, rain came down hard. The drone of the relentless rain and the constant howl of the powerful gale force wind shut all the other sounds around me. I buried myself in the comforting warmth of my bedroll. Tired to the bone, I holed up inside it till harsh weather passed late in the afternoon.

Once I could vacate my involuntary confinement, the tide was out and the mucky tidal plain blocked my exit. At the far end of the beach, I saw something that might have been a coastal bear. Behind me, in the thick undergrowth by the Wolf River, some animal was yelping pleadingly. It could have been a bear cub or a wolf pup. Dreading an encounter with its overprotective mom, I quickly glanced at the sea. That was my only way out. There, over the felluvial pan, something had set off a flock of sparking white kittiwakes. I could not see what it might have been for they were dive bombing it behind the tall rocks.

Determined to leave, I clipped a tow line to the bow of the kayak and then pushed the heavy boat into the sticky creek. Cutting the tidal plain in half, the creek was just an indentation in the smelly silt. Then, for an agonizing hour, I hauled the kayak on a long line through the fluvial pan resting some of my weight on the paddle. The thin rope kept cutting into my calloused hand. No see um flies feasted on my eyes and I even had no hand left to drive them off. If I sped up my advance, the gooey mud peeled my neoprene boots off. Just as I thought that I could not bear this any longer, I felt the bottom of the ocean drop down. I was free at last.

Scrambling into the tight cockpit, I was thankful for the extra hours of sunlight. A swarm of mosquitoes escorted me out of the muddy cove into the open sea. As I cleared a small rock outcropping, I saw the sun slowly dipping behind the horizon. Gliding across the red carpet in front of me, I swiftly made my way to the Outer Spokane Cove. Though only a mile away, my new location was a definite upgrade over the one the night before.

I beached the kayak on the white sand beach and then quickly scaled the steep sandy embankment with all of my belongings. In the fading light of the midnight sun, I stomped out the tall sharp ryegrass to make room for the kayak and the tent. It was time to call it a day. I scanned the surroundings for signs of animal danger. Nothing alerted me, so I tucked myself into a sleeping bag inside the warm tent.

Later that night, as I was trying to fall asleep, a musically inclined humpback whale swam close to the beach below. Serenading all throughout the night, he kept waking me up with his lamenting calls.. His message was loud and clear. He was ready for some whale company. I, on the other hand, was not. Like it or not, I became drawn into some kind of cetacean melodrama.

Whales, Wolves, and Others

The next day was a scorcher. I sat sweating on the white sand beach in just a bathing suit. Slitting my eyes, I looked around. The hot steamy air pulsated over the wet sand distorting my vision. Out of this late morning baking sauna a dog walked out. A dog, no, not here, I thought. Scrutinizing the approaching scrawny shape with fearful amazement, I cried wolf for it was a wolf, at least so I thought. Unafraid, bold, beautiful, but was it alone? As it trotted closer, it stopped, sniffed the air and looked in my direction with guarded hesitation. Primordial fear crawled down my spine.

Naah, no need to be afraid. Wolves are skittish, fickle creatures, I sharply reminded myself. This one here would do me no harm. But, no, it continued moseying boldly towards me. Then, it stopped, turned over a rock, munched on something unfrazzled by my presence at all. A quick bite was over, what then? Was I the next item on the menu? Reading my thoughts, the brown yellow mangy beast sized me up weighing its options. Perplexed, it bared its fangs. I stood my ground. Then, came a whimper and a howl, the wolf-like creature seemed to be striking up a conversation. At this point, I became amused. My fear was gone. Click, click, I snapped pictures. Was it really a wolf? No, it was just a curious coyote.

Time flew. Days rolled one into another wearing me down with luxuriating exhaustion. Riding ocean currents, I was chasing down my youthful dreams of formidable adventures. And the adventures did come one after another. Whales popped out of the deep to give me a sinister look, harbor seals freaked me out with their aquatic antics, seagulls fought acrobatic air battles, vicious horse flies chased my every move, and so far I lived through it all.

It was already day 10 since I had left Bartlett Cove. Food was still plentiful. I was just 25 miles away from my starting point at the gateway to the East Arm. The day barely started as I left Garforth Island. Broadsided by a strong westerly breeze, I was cutting across Muir Inlet. I knew I had to do it to escape the gnarly chop before it would be totally out of control by late in the afternoon. Arm wrenching from the start, the crossing wore me out. Just as I expected, the wind died completely the moment I reached the opposite shore.

Too drowsy to continue, I slumped my head down on the cockpit in front of me. Bad idea, I thought. What if I hit something and capsize? There, coming on my left side, was a tiny u-shaped rock with an eddy behind it. I could easily get out there. The shore looked safe from where I was at. I climbed on the rock leaving the kayak anchored to my foot in the eddy. I sprawled across the warm rock and dozed off.

Something stirred in the trees, and then a cormorant flew off the nearby rock waking me up with its squeaky grunt. I looked around. At first, I saw nothing. Trees swayed in a gentle breeze or was it a breeze that moved them? I looked harder. Down, at the bottom of a dense grove of pale red alders, was a sand color coat of an animal. A deer, for sure, what else could have been forging on grass there? Relieved, I went back to sleep.

Leaves rustled gently, a branch broke, then there was dead silence again. I was wallowing in the luxury of my soft bed at home. Dazed and confused, I dreamed on. Then I felt it. The rock became hard again. Someone or something was staring at me. It was the owner of the yellow coat. with no horns, just a round head with cute little ears. A cute little bear, I thought. A bear!!! I mumbled in disbelief.

It could not be. I robbed my eyes hoping to make it go away. But it was still there, wide eyed and still, crouching peacefully a mere 20 feet away. Its eyes shrouded by a swarm of vile no seen ums, it regarded me with guarded interest. We exchanged glances like true gentlemen meeting for the first time. Not expecting a handshake, I pulled back the kayak close to shore and slid in. The bear just stayed there unnerved by the whole experience.

The Inlets

For the next 8 days, I rambled around the various inlets of the East Arm. All these inlets were very different from one another. McBride Inlet meandered deep into mainland Alaska. Squeezed by its towering walls, chunks of icebergs drifted down into the open sea. As they calved from McBride Glacier at the head of the inlet, they whipped up monstrous tidal waves. Adam’s Inlet was a raging whitewater passage siphoning tides in and out. Whales loved to feed on herring that spawned in these treacherous fast moving waters. The least turbulent of all three, was the Wachusett Inlet. It was home to many grizzly bears and towering snow capped mountains.

Notes

In the end, the trip from Bartlett Cove to Riggs Glacier and back took just 18 days. From the turn around point at Riggs, I paddled only 20 miles back to Mt. Wright beach pick up site. There, I boarded an excursion boat bound for Bartlett Cove. As I stretched on a soft lounge chair aboard my pickup boat, I wondered what made me come to Alaska for the third time? Was it the abundant wildlife or a need for yet another shot of adrenaline? Perhaps, a little bit of both. Will I ever do it again? I am already planning to be in Juneau next summer.

The Elements

Already at the onset of my trip, it turned out that my greatest two enemies were ocean gales and foggy seas. The trip would be about combating one or the other. Early in the morning or in the middle of the night, I would strike down my camp and shove it into the hold of my kayak, to launch my kayak the moment the tides turned in my favor. Many times, as I punched through the shorebreak, rain and fog chilled me to the bone. Then I would paddle hard to keep my body from freezing.

At the less fortunate times, when, without any warning, a sheet of dense inky fog descended onto the ocean. It obliterated all navigation by sight. Not being able to discern the shore, the boulders underneath the kayak or the surging waves was extremely dangerous. Looking only at my GPS, I had to instantaneously steer the kayak far from the menacing shorebreak into the open sea. Sweeping for waves with only my ears, I had to circumvent all the violent explosions. Running aground and getting pinned on a rock could be fatal.

After an hour or so of furiously paddling I would be somewhere in the middle of the ocean with whales and orcas for my consort. High on the adrenaline, my heart beat would be high. I would breathe deeply to keep it down. For a moment's rest, I might anchor the kayak on a giant kelp bed or just drift listening to the ocean for the signs of danger. In any case, I would have to wait for the light to return.

By midafternoon, the sun would usually escape from the morning fog. The air temperature would immediately rise, kicking the katabatic winds into action. These winds would sweep down from the nearby glaciers onto the unsuspecting ocean. My wait would be over. Illuminated by intense light, the shore would come to view again. The waves could no longer play a game of hide and seek. Harnessing the wind with my back, I would coast the sea back to the safety of the shore.

Sometimes this bliss would be short lived. As the day temperatures rose, the winds would gradually turn into gales churning up the ocean swell. Having had but a few battles with the raging sea, I had little confidence in my skills as a seasoned sea kayaker.

My focus would then shift from reaching my destination to slinking back to the safety of a nearby beach. I had to time my return carefully, pausing at the right moment and paddling like a madman at the next. A breaking swell could sweep me sideways, capsizing the kayak. Then, as the shore came closer, my kayak would suddenly be rising and falling on 4-foot swells. The land and horizon would disappear behind a wall of water. I felt as thoughI might poop in my pants as I surged forward into the mayhem on shore. At last, sitting astride a racing swell, I would ride ashore hopefully not puncturing the boat.

I quickly learned that afternoon sun spelled danger. Thus, on sunny afternoons, I would have to quickly hide behind an offshore island. Tucked away, I would unpack my Mini Mo Jetboil stove and pull out a bear vault with food. Far away from coastal bears, the meal I was going to cook would not bring any uninvited guests. Being swarmed by the bloodthirsty mosquitoes was but a small price to pay to be free of the turmoil offshore.

So a pattern was born. I would ride out the tide up to the moment the heavy gale would make my trip prohibitively precarious if not outright deadly. I would hunker down in the safety of an offshore island if I thought that moving forward was not advisable. There were times when this would take more than just one day. After all, my kayak was nothing but a thin sheet of plastic riding on hope.

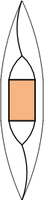

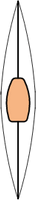

The Kayak

The Oru kayak can assume two entirely separate identities. It can either be folded into a suitcase or a kayak. Made from a rectangular piece of corrugated plastic, the kayak needs just a few additional plastic components. Morphing from a suitcase into a seaworthy vessel takes less than 10 minutes to complete. Reversing it back into a suitcase is just as easy. The thin sheet of plastic has premade folds. Once the kayak cockpit takes its form, it is zipped shut with plastic stringers. This closed cockpit boat does have a cumming for the spray skirt to keep the waves from sneaking in.

The Oru is surprisingly nimble and stable. Weighing 32 pounds, the kayak is very portable. It can even be checked in as a regular piece of luggage. This portability and flexibility comes at a cost. The thin Oru plastic is very fragile and prone to cuts. A crack in the fold can render the kayak useless as the cockpit can no longer be patched. Worse, there are no watertight bulkheads to keep the kayak buoyant in case it capsizes.

Navigation

Cognizant of Oru’s pros and cons, I had to plan my trip accordingly if I were to come out of Alaska alive. My direction and duration of travel had to be in sync with the sea rhythm. I would wake up with either incoming or outgoing tide to ride it in the direction of my travel. As soon as the current would turn, I would run for shelter in a protected cove. There, I would scramble up the beach to cook my meal for the day. Then, in the evening, I would paddle to a new place to camp for the night.

Food and Water

I tried to minimize the risk of bear encounters by limiting my meals to two a day, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. I would eat my breakfast just before leaving in the morning. During midday meals, I would have to keep the kayak anchored to my foot and close to shore but on the water. Otherwise, I would have to unpack it to move it up and down the shore with either rising or falling tide.

My menu was rice and beans or beans and rice. Occasionally nuts, energy bars, and wild berries. I used a propane gas stove to cook my meals. I boiled water for safety. I did not use filters. The water came from creeks or chunks of glacial ice.

Camping

Securing a place to camp while underway in a sea kayak began with a study of the tide app on my phone to know the size of the upcoming tide. Then, would scour the horizon for a cove or a beach that was too exposed to the open ocean. Safe landing places for the kayak were the ones that were free from razor sharp rocks or leg twisting slippery boulders.

My campsite had to be way above the tidal zone. Otherwise, a passing storm could spring up at night and completely flood it. This was critical as tides could be as high as 22 feet in this part of the world. Gauging the extent of the tidal activity had just two reassuring caveats. Strawberries and moss do not tolerate seawater. So spotting them meant the area was free of seawater. Thus, it was safe from unwelcome tides that could flood my camp.

Finding a clearing big enough for a camp and a kayak was yet another challenge. If there was a clearing, it frequently came with boulders or it was on a steep slope. There were countless times when I felt at night like a bat dangling from a tree limb or a snake strewn over rocks, but I was too tired to care.

Bears

Bears were everywhere. Brown, black, yellow, small, big and tall, they lined up the shores looking for food. I saw them close as I hugged the coastline on my way to Riggs. They were not humans so I knew they would not hunt me for a trophy or out of spite or fun. It was a refreshing feeling knowing that they were omnivores with a strong plant diet bias. As long as there were grasses, berries, or shrubs I felt inviolable.

Every bear has a “personal space”– the distance within which the bear feels threatened. This space is mood dependent and thus varies from day to day. So my survival in bear country was very luck dependent. If you enter that space, you never know how it will turn out. If I saw a sow, I would give her extra space. Female bears are especially fierce defenders of their young and may respond aggressively, if they perceive a threat to their cubs.

When I photographed bears, I used a 500mm zoom and stayed far away in my kayak. I would never pursue bears on land or water. Bears, like humans, use trails and roads. I would never set up my camp close to a trail they might use. At night, before I went to sleep, I played loud music to let bears know I was there. I kept a bear spray canister in the holster at all times while on land. Doing all of that was helpful, but by no means a guarantee of safe passage.

Safety

One of the devices I had with me was a Garmin Explorer +. It is a compact, waterproof, handheld device that utilizes worldwide coverage of the Iridium satellite network to communicate. As long as I kept my Garmin charged and on, I was never alone. At all times, I could exchange text messages with any cell phone number or email address or even share my GPS coordinates. To pinpoint my route, I synced Garmin’s maps of the areas I would paddle in Alaska to the Earthmate app on my phone. In case of an at-risk situation, I could trigger an SOS distress call to the 24/7 monitoring center, text back and forth about the nature of my emergency, and receive confirmation when help is on the way.